Government Stimulus To Reconcile COVID-19 Damages Should Be Reconsidered

COVID-19 is the pandemic causing hysteria to stretch the globe, but most relatively, it is causing a massive panic for an expected recession in the United States. Unemployment has shot up, businesses are closing, interest rates are nearing zero and the government is promising $2.2 trillion to infuse the economy with. What does this mean for the overall economy, you might ask? More specifically, we must clarify what this means and why we might be going into a recession. To answer, let’s take a dive into Macroeconomics 101:

The Law of Demand states that the amount of goods or services the consumer chooses to purchase works inversely with the price of said good or service. This is due to the “Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility.” The cheaper the product, the happier the consumer is purchasing more of that product.

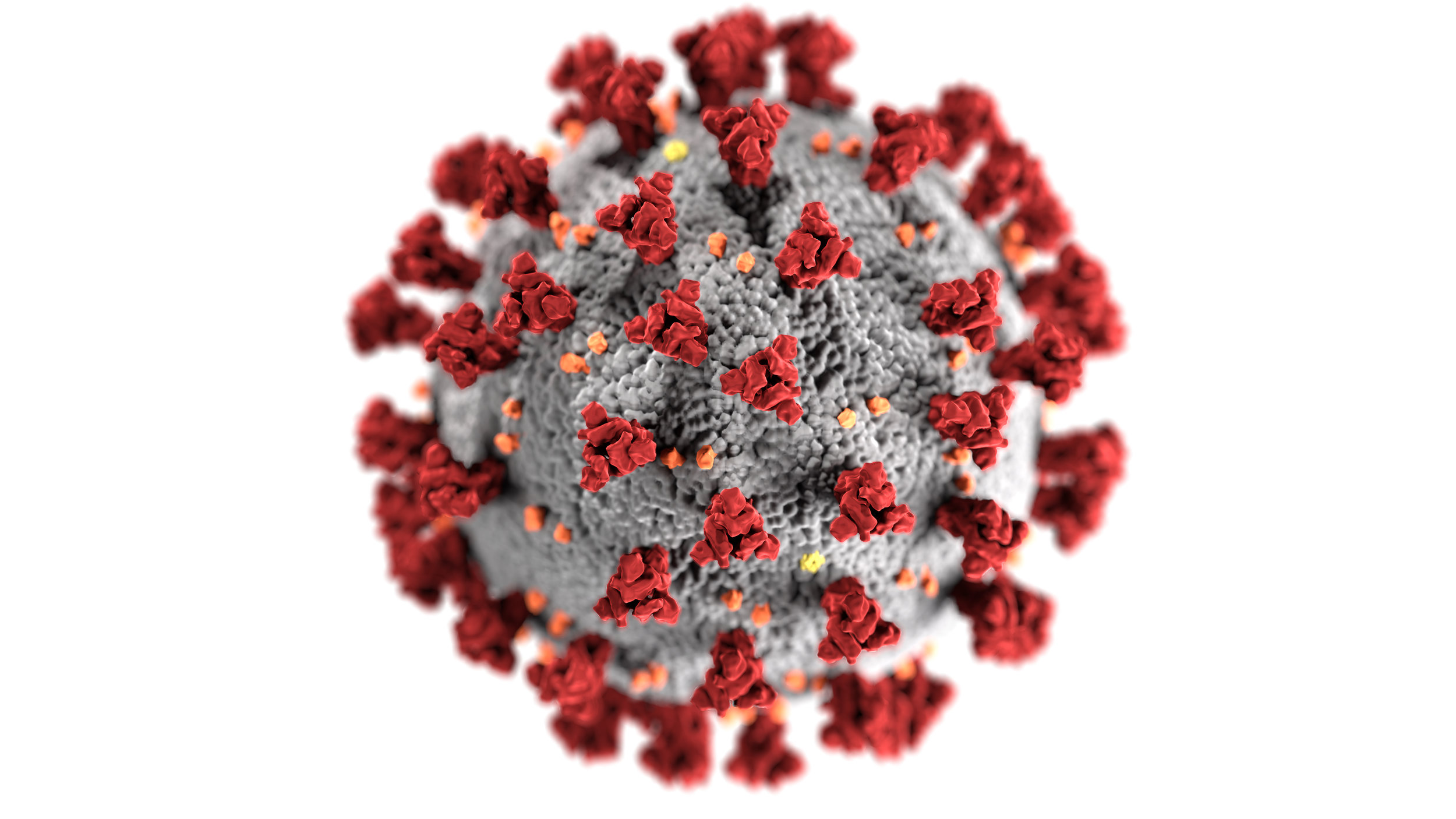

In the face of a pandemic, we are not seeing too much consumer spending. This is due to Keynesian Supply shocks we are seeing in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, newly implemented ‘social distancing’ rules, and local economy shut downs. States such as New York, New Jersey and California created a division between Essential and Non-essential workers in the labor force, telling all of the non-essential workers to go home and either work (if possible) or stay inside isolated from the pandemic outbreak. This has vastly shut-down sectors like manufacturing, hospitality and tourism, and retail. An economy with multiple sectors such as the United States has more to be worried for because of an amplified demand effect.

Figure 1.

Multiple sector economies hit by COVID-19 are hindered by a wider scope of demand decrease. If one sector of the economy shuts down, then its workers are not getting paid and obligated to save their money and/or spend it in other sectors (see Figure 1). There is greater reasoning for total spending in a multiple sector economy to contract. If some sectors of the economy get shut down, then the prices of the affected goods, or “shadow goods,” shoot up since there is fewer supply due to the supply shock of goods in that sector. We call them shadow goods because we are not presently seeing them in circulation in our given economy. This is a temporary assumption, of course, but what this does is make total consumption in the multiple sector economy more expensive. The rise in the price of shadow goods discourages spending and enters the entire economy into a negative growth path.

The workers in affected sectors are not seeing any income either, decreasing spending to the unaffected sectors. For example, if we just look at two sectors, restaurants and grocery stores, we see restaurants shut down. They cannot continue to operate at normal speeds, and offering only takeout and curb-side pick-up will not be sufficient enough to keep paying operating costs. This may result in layoffs or possibly even an outright shut-down of the business. This is the opposite for grocery stores. They must work and remain operating because they are unaffected. However, the restaurant workers who can’t work aren’t making any money, and therefore will be more inclined to spend less and save more, even at grocery stores! Instead of buying the prime beef and fresh spinach, they might turn to packaged meat and frozen greens. Point is, it’s all relative. Spillovers of demand shortages from sectors in our economy is an active agent in the case of the United States’ response to COVID-19.

Keynesian economics explains the logic that government intervention can stimulate aggregate demand and recover an economy from supply shocks and demand shortages, in the short run. In the case of COVID-19, the U.S. government’s strategy in this situation must be unique. The government can not prop our economy back to normal consumption levels by spending on their own because current spending conditions are due to the fact that the money people and businesses need are for debt and potential loan defaults. This is not the case, and this is why the expected recession in the U.S. may be worse than our government thinks.

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) is a variable in economics that represents the consumers ability to track their consumption based on their disposable income. MPC is currently, marginally down for workers in affected sectors of the economy. The laid off workers and business owners who aren’t working are the largest agents of this effect, meaning the U.S. government will have to make up for the loss of spending from these individuals especially, but government spending doesn’t help these agents. The stimulus and transfer payments do help, however, these payments won’t just go to these individuals as income. They will come as debt relief for overdue bills and fixed expenses. Therefore, this may only prevent consumer spending from declining more, going against the laws of Keynesian economics where consumer spending should get a boost.

The problem isn’t solved by fiscal stimulus.

When state governments shut down non-essential businesses, not only are workers not receiving income, the business isn’t either. All of a sudden, operating income is non-existent, and the fixed costs that businesses endure to remain afloat will bear massive consequences. Not only will businesses bring down other businesses due to the Keynesian supply shock forces seen in Figure 1, but businesses that shut down lay off workers because these operating costs are taking too much out of them. This is a new, endogenous form of supply shock that we are witnessing. With this, there are two options a business can decide on. They can continually operate while holding on to their workers at a loss, or let workers go and lose out on future profits. Business owners are facing a point where taking on the costs of keeping business operating and workers working is unequivocally pointless, unless there are different implementations by the federal government.

Mechanisms such as interest rate cuts and tax reductions could provide the necessary avenues of economic relief to this broken system. With the right levels of small business debt relief through these mechanisms business owners will be able to lean on future profits by taking on debt with more confidence and keeping their workers working and happy, given safety measures are secure.

Real consumer spending is expected to contract at -4.7% year over year, meaning these are real forecasts for the foreseeable future. Businesses are expected to get hit and according to Dr. Daniel Bahman of Deloitte, there is a 50% probability of a COVID-19 induced recession and 30% probability of a financial crisis and deep recession. Businesses are going to lean on financial relief through the COVID-19 pandemic, but the forms in which they come need to be realized by the government before stopping at ineffective fiscal policies. The laws of Keynesian economics show that the supply shocks we are seeing are unique and need to be addressed according to fiscal stimulus that minimizes these propped up effects.

References

Guerrieri, et al. “Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages?” NBER, 2 Apr. 2020, www.nber.org/papers/w26918.

“United States Economic Forecast.” Deloitte Insights, 27 Mar. 2020, www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/us-economic-forecast/united-states-outlook-analysis .html.

Liberto, Daniel. “Intertemporal Choice Definition.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 26 Feb. 2020, www.investopedia.com/terms/i/intertemporalchoice.asp.