The Biggest Challenge for Distributing Vaccines Will Give You Chills

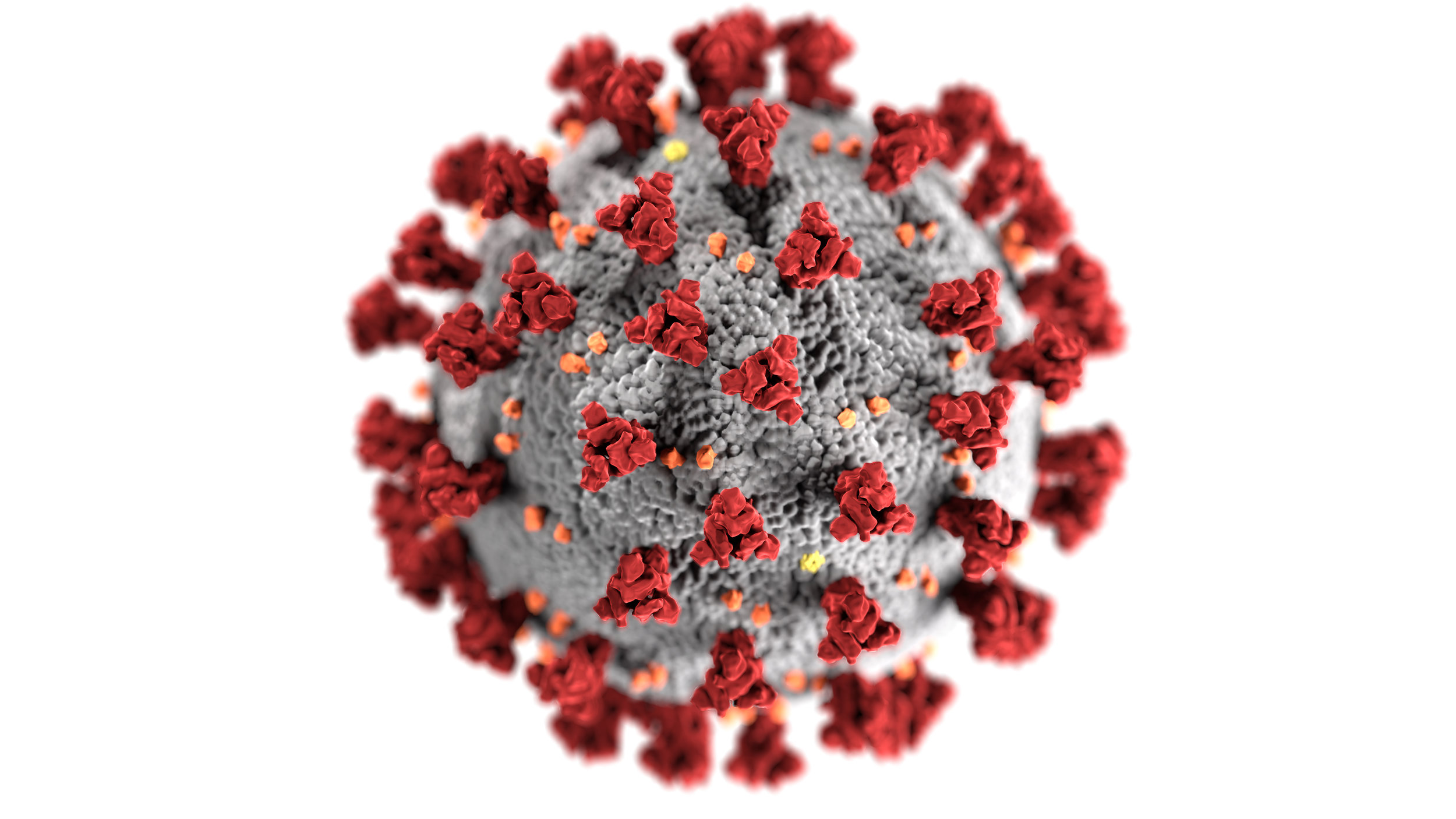

Pfizer and Moderna are the frontrunners for an m-RNA vaccine for COVID-19 and are facing massive challenges in supply chain structures for their products. Cold storage needs are among the main concerns and analysts at SVB Leerink, a Boston investment bank, are afraid the two pharmaceutical companies won’t be able to meet regulatory guidelines. However, no mRNA vaccines have ever been approved, so Pfizer and Moderna are under pressure as both are racing to make history.

First, what are m-RNA vaccines and how do they compare to traditional vaccines? Traditional vaccines train the body to recognize the proteins in cells that viruses produce. Once injected, the viral proteins provoke the immune system and mount a response (a.k.a. immunization). mRNA, on the other hand, acts as a ‘template’ for the viral protein to build once the vaccine is injected. The vaccine itself essentially codes DNA in a way to build infectious proteins. Since the chemical interaction is extremely sensitive and complicated, a few things need to happen to handle ready-made vaccine products, one of which being temperature regulation.

Pfizer’s vaccine hopeful reportedly needs to be held at -94°F and can last for only 24 hours at refrigerated temperatures between 35.6°F and 46.4°F (Blankenship, 2020). Most other vaccines of this chemical nature can be held at refrigerated temperatures for months. SVB Leerink analysts believe distribution will be the most difficult task, and predict Pfizer will only be able to distribute to designated government spots, according to product shipping and storage requirements. Pfizer was a part of a $1.95 million contract with the U.S. government for 100 million doses initially, and possibly 500 million additional doses down the line. Moderna is showing that their vaccine can be stored at -4° Fahrenheit, having a big leg up over Pfizer. This temperature is comparable to home freezers. Moderna took $2.5 billion in U.S. funding for both the development and supply of its vaccine. It even took a $1.5 billion work order from the U.S. for 100 million doses, despite not even having a final product (Blankenship, 2020). Both companies are under the gun since they both promised hundreds of millions of vaccines within months of a potential approval.

To take a closer look at the process of controlling vaccine temperatures, we can look to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendations in the “Controlled Temperature Chain” (CTC). The CTC is reported to a WHO advisory committee called the “Immunization Practices Advisory Committee” (IPAC). First, licensing for CTC is approved by the origin country’s national regulatory authority. For the U.S. it’s WHO. The approval process starts in the lab and has to pass stability testing, then goes through national regulatory authority for a CTC “label” that specifies conditions of use, then it needs to be prequalified by the WHO, and finally, the government where the vaccine will be used must give consent to use it (WHO: CTC Infographic, July, 2018). The main difference between controlled temperature chains and a traditional cold chain of vaccine distribution is that CTC does not require ice packs in the vaccine packaging. Instead, there are peak temperature threshold indicators that monitor exposure to heat on each vaccine bottle within a main freezer. This typically reduces the risk of the vaccine freezing and allows the health workers to regulate the temperature manually after proper training. CTC heavily involves health workers, and when implemented correctly, it preserves the safety and potency of the vaccine. CTC gives distributors easier outreach to the masses, which makes the pharmaceutical’s job easier. Moderna and Pfizer’s biggest concerns is the outreach challenge, so using CTC could pose a major advantage if they ever get to the distribution process.

Cost is another issue. Vaccines are considered commodities and are traded goods in an international market. Moderna and Pfizer are pricing their vaccine in USD since they’re in contract with the U.S. If they were to sell internationally, the price point and cost of this program could be substantially different than the $2.5 billion facility Moderna scored (WHO). Tariffs on commodities in certain countries could pose as a major obstacle. Consider, for example, the United States poses a 25% tariff on all commodity exports to China. For $100 worth of vaccines sold to China, the cost would come around to $125. In the case of a successful vaccine, countries could come into conflict over this situation, leading to less cooperation across the global trade landscape (WHO, 2008). In considering the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine for each country, tariffs only appear in some, if any cases. There are other costs associated with the production and distribution of the vaccines. They include supplies like vials, chemicals, containers and more, as well as training resources for health professionals administering the vaccine (The World Bank, 2010). Of course, the U.S. anticipates a government framework to figure these costs out. Distribution costs with the specific conditions Moderna and Pfizer’s potential vaccines must be taken care of will be most tricky and costly. This is also only in consideration of the initial distributions.

Works Cited

Blankenship, K. (2020, August 28). Pfizer, Moderna's coronavirus shot rollouts could freeze up, experts say, citing cold-storage needs. Retrieved October 07, 2020, from https://www.fiercepharma.com/manufacturing/pfizer-moderna-s-covid-19-shot-rollouts-could-be-ice-as-analysts-question-cold?utm_source=morning_brew

Controlled temperature chain (CTC). (2018, July 12). Retrieved October 07, 2020, from https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/supply_chain/ctc/en/index3.html

Immunization Planning and Financing. (2019, September 20). Retrieved October 07, 2020, from https://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/financing/en/

WHO Guide on Standardization of Economic Evaluations of Immunization Programmes. (2019, October 17). Retrieved October 07, 2020, from https://www.who.int/immunization/documents/who_ivb_19.10/en/

Edited by Jaret Prothro