A Beginner’s Guide to Theropods, Part 2: Crests, Horns and Sails

The First Jurassic Theropods, and the World They Inherited

The Early Jurassic World was a very uniform one. After the extremes of heat and drought that characterized the Triassic, a brief period of global cooling had reduced their therapsid and croc-line competitors to a handful of small mammals and lizardlike creatures and allowed the formerly restricted dinosaurs to spread throughout the world (Dunne et al). With the continents joined together, there were no major barriers to their dispersal, and so for the first time in dinosaur history, faunas the world over looked much the same (Holtz). Some faunal elements would have been familiar, if rare, parts of a Late Triassic ecosystem: long-tailed pterosaurs in the air, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs in the sea, bipedal prosauropods and small coelophysids on land. Others were more novel: elephant-sized sauropods, bipedal and armored ornithischians, and hunting them all, the first truly large (6m+), apex-predator theropods.

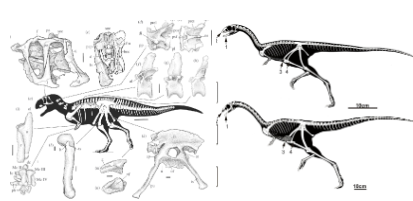

Left: Crested Cryolophosaurus (Hartman) hunted the prosauropod Glacialosaurus in the coastal forests of Antarctica, as its contemporary Dilophosaurus hunted Sarahsaurus in the deserts of Arizona. Right: Saltriovenator (Dal Sasso et al); known material highlighted.

Left: Crested Cryolophosaurus (Hartman) hunted the prosauropod Glacialosaurus in the coastal forests of Antarctica, as its contemporary Dilophosaurus hunted Sarahsaurus in the deserts of Arizona. Right: Saltriovenator (Dal Sasso et al); known material highlighted.

These early predators, although smaller and less spectacular than the ones that followed, had a set of adaptations all their own. Most conspicuous of these were their visual displays: Dilophosaurus has a pair of crests, Cryolophosaurus had a pompadour, and later Ceratosaurus had not only three horns - two above the eyes and one on the nose - but a row of osteoderms running down its back. In life, these crests and horns might have been covered with keratin and brightly colored, but (with the exception of Ceratosaurus) they were filled with air sacs, and probably too fragile to be used in intraspecific combat (Marsh and Rowe).

Another strange feature - one that Dilophosaurus is (in)famous for - is a jaw with a “kink,” a gap in the tooth row. This is a primitive feature - already present in Coelophysis - exaggerated, giving the skull a strange, almost fragile appearance (Welles). Historically, it was thought that the skull was too weak to do much damage, that its long arms did most of the killing, or that it was specialized for scavenging or eating fish (Milner and Kirkland). Michael Crichton, author of Jurassic Park, famously suggested that its long, thin teeth were adapted for a venomous bite (the bony frill was a movie invention). More recent studies have shown that the jaw is stronger than it appears (strong enough to leave marks in the bone!) and that its front edge was built to endure the loads exerted by smaller, struggling animals (Marsh and Rowe; Therrien et al.).

Meet the Ceratosaurs

Among this first wave of predators was the Italian Saltriovenator, which, from what little is known of it, appears to be the earliest known ceratosaur. Primitive ceratosaurs, best known from the late Jurassic Ceratosaurus, were mid-large, largely unspecialized theropods that, as far as we know, were never particularly common. In the Morrison Formation of Western North America, Ceratosaurus had to contend with the larger, much more common Allosaurus, and the equally rare Torvosaurus. How it did this is uncertain; it may have preferred wetter, more forested habitats, like leopards do today (Changyu). But sometime in the Jurassic, as the supercontinent began to break up, something strange happened: the ceratosaurs became southern endemics.

Eoabelisaurus, the oldest of the southern-endemic abelisauroids, lived in the mid-Jurassic Asfalto Formation of Argentina alongside the more derived megalosaur Piatnitzkysaurus and allosaur Asfaltovenator. This was the beginning of a new wave, one that would characterize the later Jurassic and early Cretaceous. The globe-spanning megalosauroids and allosauroids, while producing enormous spinosaurs and carcharodontosaurs, did not see the end of the Cretaceous, while the smaller, more geographically restricted abelisauroids continued in wide diversity until the end. Ceratosaurs were among the first to show up and the last to leave.

Left: early Eoabelisaurus (Rauhut and Pol). Right: ontogeny of Limusaurus (Wang et al.)

Abelisauroids, as organisms tend to do when isolated, became extremely diverse, producing not only well-known macropredators like Carnotaurus and Majungasaurus, but also much smaller, snaggletoothed noasaurs, and hypergracile, beaked elaphrosaurs. Limusaurus, from the late Jurassic of China, is known from a complete growth series, showing that young individuals retained teeth that got lost as they got older, shifting to a herbivorous diet. Noasaurs were built for speed, and trackways show at least some were functionally monodactyl (Langer et al).

Abelisaurids themselves look highly specialized, with their weird combination of seemingly contradictory features. Their skulls were short and stubby - nearly as tall as they were long - and covered over in rough, bony growths, including on the eye socket! Despite this, their lower jaws weren't particularly robust, and their teeth were tiny. In Carnotaurus, these growths grew into a pair of bull-like horns that may have been used to fight off competitors for food or mates, supported by a powerful neck and a spine braced against shocks from the side (Novas, in Holtz et al). Abelisaur legs varied in proportion, from short and stubby in Majungasaurus to long and slender in Carnotaurus, but they were all more robust than in most other theropods. They were probably built for power over speed, as they struggled with the slow-moving sauropods that dominated the southern continents during the Cretaceous (Holtz et al). Finally, their arms were downright vestigial: the whole upper arm was reduced to a pair of wrist bones, the elbows were immobile, and the outer fingers were reduced to splinters (Rauhut and Pol).

Stiff Tails and Big Claws

All theropods from this point on are known as tetanurans, or “still tails.” The name comes from a series of projections, found on most or all of the tail vertebrae, that help lock the tail together, allowing it to be used as a counterbalance for tight turns (a similar system of muscles is found in big cats - Holtz.) This is famously taken to an extreme in dromaeosaurs, but it also serves as the beginning of the knee-based locomotory system in birds - as the tail gets decoupled from the leg muscles, it’s freed up to serve other functions and eventually drops off (Pitman).

Another tetanuran feature is a large, three-fingered hand. While in more primitive theropods (some more than others), the hand was small and unspecialized, tetanurans make use of a full range of specializations, from the killing claws of allosauroids to the meat hooks of tyrannosaurs, the scythes of therizinosaurs and the wings of birds (Holtz). First of these is the short, robust forearm of megalosauroids, armed with a big, powerful thumb claw.

The megalosaurs of the Middle Jurassic were the first global radiation of tetanuran predators. Starting as mid-sized, rather generic-looking predators, they spread alongside their allosaur contemporaries before dwindling into rare forms like the Late Jurassic “big bruiser” Torvosaurus (Rauhut et al). But they must have survived somewhere because early in the Cretaceous, they reentered the picture as the specialized fish-eating spinosaurids.

Composite of known Spinosaurus material (GetAwayTrike), showing probable proportions… probably.

Everyone agrees that spinosaurs, with their big, hooked claws and long, slender skulls with rosettes of conical teeth, grabbed and held onto struggling fish (Holtz). Pretty much everything else is contentious. How much fish did they eat? Wherever they're found (everywhere except North America - so far), it's invariably in wet environments, sometimes with giant fish like the 5-meter North African coelacanth Mawsonia, or even freshwater plesiosaurs (Holtz)! But they ate land animals too: the English Baryonyx was found with half-digested Iguanodon bones alongside fish scales (Charig and Milner), and a Brazilian pterosaur even had a spinosaur tooth embedded in its vertebrae (Buffetaut et al). The 14-meter Spinosaurus, living in the swamps of North Africa, was probably a more dedicated fisher than most, avoiding competition with the even bigger allosauroid Carcharodontosaurus.

How did they hunt? Many spinosaurs had fairly typical theropod proportions, and probably hunted much like big wading birds (Hone and Holtz). But the very atypical Spinosaurus, with its tiny legs, meter-long spines, and deep tail, must have been doing something unusual. Despite its popularity, Spinosaurus is still a poorly-known animal, and its proportions are very uncertain. When large portions of its skeleton were put together in 2014 (Ibrahim et al), it was reconstructed as a front-heavy quadruped. The legs, however, are denser than they look (Henderson), and what little we know of the arms seems to show they weren't particularly suited for weight-bearing. Some researchers (Fabbri et al.) argue these dense bones were adaptations for a diving lifestyle, while others (Sereno et al.) think the sail made it poorly balanced and that it would've needed to tread water constantly to keep from tipping over. Hone and Holtz also argue the placement of the nostrils was more like that of a snout-dipper than a subsurface swimmer. And the tail? They think it was a poorly-muscled display structure, more like that of a basilisk than a crocodile.

But the most conspicuous thing about Spinosaurus is its sail. What was it for? It must have made a formidable display for intimidating rivals and attracting mates (Hone and Holtz). If it were full of blood vessels (which Ibrahim doubts), it would’ve been an effective way to radiate heat. Spinosaurus, like the similarly sailed sauropod Rebbachisaurus and iguanodont Ouranosaurus, lived near the equator during the hottest part of the Cretaceous. At the time, there was a current around the equator, and without any barriers to disperse it to higher latitudes, the ocean - and so the land - stayed warm (Holtz). But around 95 million years ago, the world began to cool, and the shallow, continent-spanning swamps of the Early Cretaceous began to drain, bringing Spinosaurus, the last and largest of the spinosaurids, with them. Changing continents and climates helped dinosaurs diversify, but they could also bring about their extinction. Next time, we'll look at one group that developed alongside the spreading continents, until the same geologic forces that brought about their global success led to their very local downfall.

Image credits

Cryolophosaurus by Scott Hartman from skeletaldrawing.com/theropods

Spinosaurus from deviantart.com/getawaytrike/art/Waterside-wanderer-840206899

Works cited

Emma M. Dunne, Alexander Farnsworth, Roger B.J. Benson, Pedro L. Godoy, Sarah E. Greene, Paul J. Valdes, Daniel J. Lunt, Richard J. Butler. Climatic controls on the ecological ascendancy of dinosaurs. Current Biology, 2022; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.064.

Holtz, Thomas (2021). Lectures for GEOL-104. Dinosaurs: A Natural History. University of Maryland. youtube.com/playlist?list=PLzO5aKfW25o1YGvDbUJC8yT9mD0TQn3MX

Marsh, A.D.; Rowe, T.B. (2020). "A comprehensive anatomical and phylogenetic evaluation of Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda) with descriptions of new specimens from the Kayenta Formation of northern Arizona". Journal of Paleontology. 94 (S78). doi:10.1017/jpa.2020.14.

Welles, S.P. (1984). "Dilophosaurus wetherilli (Dinosauria, Theropoda), osteology and comparisons". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 185.

Milner, A.; Kirkland, J. (2007). "The case for fishing dinosaurs at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm" (PDF). Survey Notes of the Utah Geological Survey. 39

Therrien, F.; Henderson, D.; Ruff, C. (2005). "Bite me – biomechanical models of theropod mandibles and implications for feeding behavior". In Carpenter, K. (ed.). The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press.

Dal Sasso, C; Maganuco, S; Cau, A. (2018). "The oldest ceratosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda), from the Lower Jurassic of Italy, sheds light on the evolution of the three-fingered hand of birds". PeerJ. 1 (1): e5976. doi:10.7717/peerj.5976

Diego Pol & Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2012). "A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1804): 3170–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660.

Changyu Yun (2019). "Comments on the ecology of Jurassic theropod dinosaur Ceratosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) with critical reevaluation for supposed semiaquatic lifestyle". Volumina Jurassica. XVII

Wang S, Stiegler J, Amiot R, Wang X, Du GH, Clark JM, Xu X. Extreme Ontogenetic Changes in a Ceratosaurian Theropod. Curr Biol. 2017 Jan 9;27(1):144-148. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043. Epub 2016 Dec 22.