A Brief Introduction to the Semitic Languages

October 13, 1988.

In all its ceremony and prestige, the Swedish Academy announced its choice for the Nobel Prize in Literature, bestowing the medal to Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz. Writing in Arabic, Mahfouz’s existentialist works in landmark publications like The Cairo Trilogy were the first of its language to receive the award. “His production has meant a powerful upswing for the novel as a genre and for the development of the literary language in Arabic-speaking cultural circles,” the Academy stated. “The range is however greater than that.”

Indeed, the Academy was addressing a profoundly essential fact: The influence and scope of the Arabic language and its works of literature, the most widely-spoken of the Semitic branch of languages. Arabic is spoken by roughly 65,000,000 people from the Arabian Peninsula and across North Africa and Central Asia, from Morocco to Iraq, and all around the global Arab diaspora (Wood).

In addition to Arabic, there are dozens of Semitic languages, including Hebrew, Amharic, Tigre, Maltese, and Aramaic. Semitic languages are in turn a subbranch of the Afro-Asiatic constellation. Their proximity to major historical developments, such as the development of the Abrahamic religions (original texts of which were written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Classical Arabic) means that these are among the most discussed, examined, and preserved languages in the field.

The purpose of this article is to present these languages, their history, and their significance. These languages are not mutually intelligible, meaning that they cannot be understood from one language to another without the aid of translation, though they share etymologies (Wood). Even within Arabic itself, there is tremendous diversity and issues of intelligibility. This results in a bright and vivid bouquet of languages.

Yet before we go too far into this introduction, we must look at the characteristics of these languages. The Semitic languages are unique in the world’s morphological architecture. While many languages feature a system in which prefixes or suffixes are attached to a base word or morpheme, Semitic languages are nonconcatenative, meaning that the root itself is reconfigured. We see this in isolated incidents in English. The word goose, for example, is pluralized as geese. Semitic languages make tremendous and well-developed use of nonconcatenative morphology. In Arabic and Hebrew, meaning is ascribed to (most commonly but not exclusively) triliteral roots with a semantic meaning attached to the roots. The suffixes and prefixes – referred to as transfixes in Semitic contexts – are ribboned through the roots. Regular Arabic roots consist of three consonants. These regular roots and their transfixes can be expected to pluralize or conjugate with some predictability. However, irregular roots (which may consist of a second or third root letter being the same or if one of the roots is a vowel) do occur and affect the morphological shifts of a word (Wightwick).

Let us pick up an example of an Arabic verb with a regular conjugation. If we look at the triliteral root of [f], [t], and [hʕ], we see that all words that feature this root are related to the concept of opening. Thus various transfixes are woven through to create the word miftahʕ, which means “key.” Using the same roots but now conceptualizing it as a verb, we see that the word “to open” utilizes a suffix: liftahʕ. In this example, we can see that the [f], [t], and [hʕ] remain but the presence of individual transfixes changes the concept into a verb or noun or any other part of speech.

Transfixes are therefore a crucial concept in understanding how Semitic languages function. Because of the unique way transfixes are threaded through triliteral roots in Semitic languages, some scholars advocate the term abjad when referring to Semitic writing systems instead of the Greek-derived alphabet (Prochwicz-Studnicka, 54). An abjad differs from an alphabet in that the graphemes are mostly consonants with diacritics representing the vowels. To return to Arabic as an example, we see that it features twenty-eight letters, primarily consonants. The diacritics are mostly removed in books and print media but are included in textbooks. As an example, the diacritic placed above the consonant known as fatha indicates that the vowel following the consonant is to be pronounced as a short /a/.

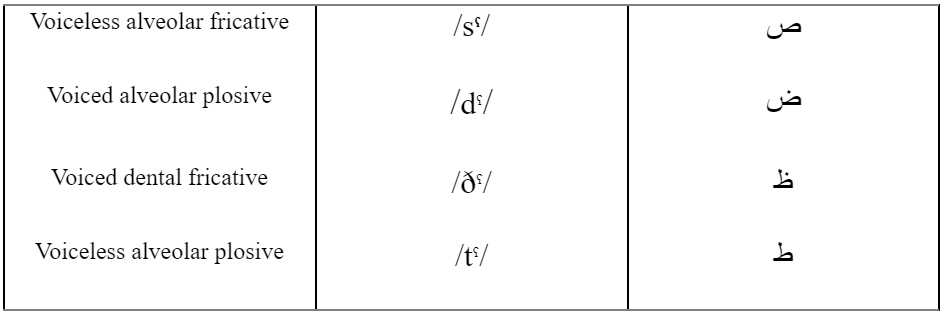

As we see in other Semitic writing systems, the abjad is written right to left. In Arabic, there is a phonological inventory consisting of a few sounds that are not in the English language and are represented uniquely by the Arabic script. These would be the so-called “emphatic” consonants:

As we can see in the middle column, there is a pharyngeal/glottal sign just to the right of the standard International Phonetic Alphabet phonemes, indicating that the throat and glottis tighten as the sound is pronounced. The Arabic abjad was possibly developed from the Nabatean script, which may have spread west via either Syria or Mesopotamia between the 4th century BCE to circa 100 CE (Prochwicz-Studnicka, 63).

The earliest attested member of the Semitic family is Akkadian, which has been alternately referred to as Assyrian and Babylonian (Huehnergard). Written in cuneiform and preserved on clay that has been excavated from all over Mesopotamia, Akkadian was spoken between the third and first millennia BCE (Akkadian).

Researchers have made progress in fashioning a portrait of Semitic history using the comparative method, which involves reconstructing parent languages by looking at the etymologies and grammars of daughter languages. But archaeological evidence played as much of a part in understanding the development and migration of Semitic languages as the comparative method has. Now, modern mathematical analyses have been conducted by Kitchen and colleagues (2009), who studied Semitic lexical data using Bayesian methods to track the dispersal of the family. They concluded that the ethnic and linguistic Semitic populations originated in the early Bronze Age from southern Arabia.

More recent inroads have been made with the reconstruction and revitalization of Hebrew as a spoken language, making it the most successfully revitalized language in history. By the end of the second century BCE, Hebrew was a dead language (Devlin) but remained a written text used in religious ceremonies in Jewish communities worldwide. In the Middle Ages, there were occasional attempts to revitalize Hebrew via various literary feats, including plays and operas and translations of books from Arabic and Latin. But in 1879, medical student Eliezer Ben Yehudah proposed founding a community in Palestine with Hebrew as its base language. His own son became the first Hebrew-speaking child. Rabin (1963) describes the language as being recreated “piecemeal” but that the driver of its modern usage has been through schools throughout the region and by 1914, the language was dominant. The vocabulary exploded from 7,000 preserved words to over 50,000.

Today Hebrew literature spans all genres and is widely translated. Notable authors include Amos Oz, David Grossman, and Zeruya Shalev. Common themes have shifted from a multi-territorial perspective (as the Jewish diaspora had been spread out across the world) with themes including Yiddish speech and life in shtetls to an Israeli identification (Israeli Hebrew Literature).

From Akkadian to Arabic, Phoenician to Hebrew, the Semitic languages are among the oldest recorded and most studied language families on earth. These languages are morphologically distinct but have gone on to produce right bodies of literature and historical heft. Semitic-speaking peoples have existed at the heart of major historical events beginning in Mesopotamia and continuing through to even our modern sensibilities, as we see with the case of Mahfouz and his accomplishments on the world stage.